The activist community that confronted ICE in Chicago has quieted down for the winter since ICE commander Gregory Bovino hightailed it out of town with 100 of his 200 military combatants. Southern activists report that ICE is wreaking havoc on the streets of New Orleans and other Gulf Coast towns while training the 10,000 newly-enrolled ICE recruits. In the Upper Midwest, we’re like mama bears and cubs in hibernation. We’re squirreling away our esprit to ready ourselves for the war we expect ICE to launch over the threshold in the spring.

Oh, there are cadres of fresh revolutionaries protesting against high property taxes at winterized town halls. Indivisible and other groups are keeping the newly activated engaged with Happy Hours, Coffee Hours and Sound Baths. And eager canvassers are stepping out in the cold to knock on doors for their favorite state and local candidates.

llinois’ 2026 primary is March 17. In times past, a St. Patrick’s Day election meant a big turnout at the polls. Can you guess why? Yeah, a lot of people took the day off for the parade and voted afterwards. But Illinois Governor Pritzker has told us that Bovino and his returning troops may try to disrupt our elections. What does that mean?

No one has a clue.

Amidst all this dread of the future present, I received an unexpected message about my life story that put the worries of the world on the back burner. In 2020 Tortoise Books Chicago published a memoir I’d written thanks to the encouragement of friends.

A few years after I retired I attended a poetry reading at the Museum of Contemporary Art. Shuffling up to Poet/Author/Moviemaker Kevin Coval, I disclosed, “I wish I could write”.

“Everyone can write. Everyone has stories to tell,” Kevin responded. “Come Saturday afternoon to the writing class. It’s free.”

Kevin and the others welcomed me, a much older student, into the upper room of significant creatives. One day he introduced me as “one of our writers,” and a bolt-of-lightning zipped around my bones.

Beth Finke, memoir writing teacher extraordinaire, praised my weekly essays while x’ing out the “weak” verbs and extraneous paragraphs. Writing expended a lot of brain energy and I often gave up from exhaustion. Then Beth would assign an energizing prompt like, “the tune you most remember from childhood” (Elvis’ Hound Dog). Poor thing had to listen to every detail of every step in the long saga of getting my book published.

Vivienne, an accomplice in many adventures, insisted I write a book so she could make a movie about my life. This seemed preposterous, but slipped into the maybe compartment when she wrote, produced and directed her full-length feature, “Dare to be Wild” (Netflix). It still seemed preposterous because as a friend asked me recently, “Is your life that interesting?” No. Yet, Kevin Coval attests every life is interesting.

The unexpected news I received this week puts the idea of a production, based on my book, on the front burner, in the cards, out front, on center stage, in the spotlight, on the radar, on a winning streak, ahead of the game, beating the odds, nailing it, on fire.

Knock. On. Wood.

room or home or even all the gory details about my parent’s drinking. It means to write that I wished my mother was more like I-Love-Lucy or that on most mornings I put my finger under her nose to test for life.

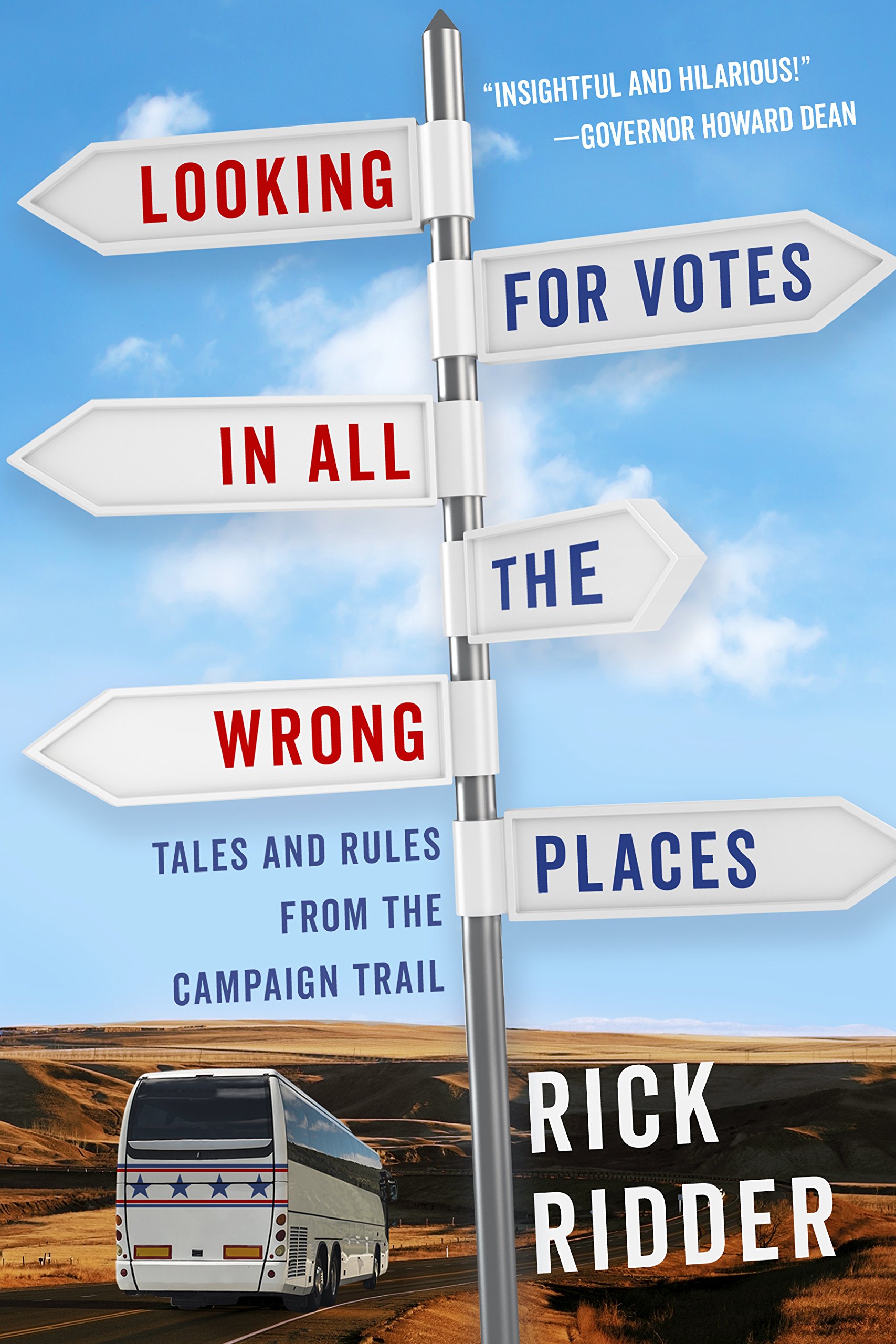

room or home or even all the gory details about my parent’s drinking. It means to write that I wished my mother was more like I-Love-Lucy or that on most mornings I put my finger under her nose to test for life. small way. We both survived the 1980s Gary Hart presidential campaigns. So when it comes to making room on the shelves for other sympathy books, the ties that bind keep Rick’s book in place.

small way. We both survived the 1980s Gary Hart presidential campaigns. So when it comes to making room on the shelves for other sympathy books, the ties that bind keep Rick’s book in place.