A crow caws in the gingko tree on the corner. The rising sun shines through the outdoor tree branches. Their shadows dapple my bedroom walls.

I wake early to catch the glory of each day’s wall art, to meditate with the trees in their seasons. Outside, Ozzy the dog and I stop long enough under the gingko tree to allow its fanning leaves to breathe a fresh day into our early morning walk.

My favorite place is anywhere there are trees.

My favorite place is anywhere there are trees.

I love them for all the usual reasons: pretty, green, shade. The deciding factor on my condo purchase 15 years ago was the swaying branches outside the wall-to-wall windows. My home is on the 3rd floor of a 20-story high-rise overlooking Lake Michigan. When I first saw the place, the three ash trees in the parkway had reached a height equal to the 4th floor.

It was like living in a treehouse.

Last year the City of Chicago’s Forestry crews euthanized my treehouse. The ashes were slowly killing themselves by feeding Emerald Ash Borers, those exotic hungry beetles from Asia. I mourn my ash trees. I thought they were immortal.

My mother, Agnes, taught me the pragmatism of trees. Stacy was born 11 years after me, and Agnes insisted I walk my baby sister around on sunny days. Her constant reminder stays with me, “Be sure you stop under the trees so the baby can see the shadows swaying.”

“Women should always have babies in the beginning of summer,” Agnes often said, “in case they are colicky, they will be soothed by leaves swaying in the trees.” She muttered “idiot” under her breath anytime another mother announced the birth of a baby in any month other than early summer.

And indeed, three of her four babies were born in May, June and July. She pretended she planned it that way.

My one and only baby, Joe, was born in May. His 1st summer was spent on his back under the trees outside in a baby carriage. Inside, he spent his time in a crib under a window of trees, syncopating his first gurgles with the sound of leaves rubbing together in the breeze.

Agnes was right about nature’s tranquilizer for infants, but she never claimed it worked for adults. She wouldn’t have been caught dead contributing such unsophisticated, sappy remedies to adult conversations. Her tranquilizers were beer and scotch and later, valium. She spent some of the last years of her life demented from these potions and gazing at the trees in verdant Vermont.

Trees soothe me anywhere, in any season. Joe absorbs tree balm while minding his wooded property. Carl Jung tells us Agnes simply passed on the inheritance – the collective unconscious of Irish tree worship that supposes tree fairies live in high branches watching over us. My mother’s life was rooted in addiction that mimicked a life-sucking aphid. Yet, she uttered words that gave me and my son our love for trees, a priceless, ancient, tranquilizing inheritance.

What’s this? We never ordered a CT scan.”

What’s this? We never ordered a CT scan.” Here comes a German Shepherd tethered to a small athletic woman. Great. I’ll have to hold Ozzy tight. I wish he’d stop trying to defend me from big dogs.

Here comes a German Shepherd tethered to a small athletic woman. Great. I’ll have to hold Ozzy tight. I wish he’d stop trying to defend me from big dogs. “Oh yeah?” says the blonde, “What about you?”

“Oh yeah?” says the blonde, “What about you?”

clay castle. Looking atop the turret one sees huge cement eggs. The exterior walls are peppered with what foreigners think are baked dinner rolls, but Catalonians know the scatological Dali created the organic sculptures to resemble excrement pies. The aphrodisiacs inside include Dali’s surrealistic art, holograms, a vintage inter

clay castle. Looking atop the turret one sees huge cement eggs. The exterior walls are peppered with what foreigners think are baked dinner rolls, but Catalonians know the scatological Dali created the organic sculptures to resemble excrement pies. The aphrodisiacs inside include Dali’s surrealistic art, holograms, a vintage inter active Cadillac and his crypt. We frittered away longer than planned and in the end found Secretary Riley and his wife, “Tunky”, resting in the Mae West living room.

active Cadillac and his crypt. We frittered away longer than planned and in the end found Secretary Riley and his wife, “Tunky”, resting in the Mae West living room. thirst dragged us to a round table full of tea roses and peonies overlooking the dry Spanish countryside. Yes, yes! We agreed to start with plates of Iberian ham. The shared plates would dish up seafood croquettes; rice with sea cucumbers, rabbit and sausage; clams with candied tomato & lemon grass. The chef had prepared fresh Catalan custard for dessert.

thirst dragged us to a round table full of tea roses and peonies overlooking the dry Spanish countryside. Yes, yes! We agreed to start with plates of Iberian ham. The shared plates would dish up seafood croquettes; rice with sea cucumbers, rabbit and sausage; clams with candied tomato & lemon grass. The chef had prepared fresh Catalan custard for dessert.

rose up, then moved to another spot, re-dampening the towel when it dried out. Her eyes winced at the uprising of clean hot steam. The acrid smell of damp cotton or wool down below flared her nostrils. As she conquered the wrinkles at hand her furrowed malcontented brow smoothed out. Agnes’ younger sister, Joanne, after a few bourbons always eulogized her with, “Your mother loved to iron.”

rose up, then moved to another spot, re-dampening the towel when it dried out. Her eyes winced at the uprising of clean hot steam. The acrid smell of damp cotton or wool down below flared her nostrils. As she conquered the wrinkles at hand her furrowed malcontented brow smoothed out. Agnes’ younger sister, Joanne, after a few bourbons always eulogized her with, “Your mother loved to iron.”

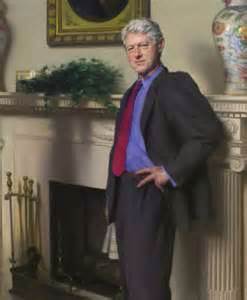

1991 I abruptly left Chicago for Arkansas to work as Clinton’s campaign scheduler, a grueling job that required 24/7 attention. One cold January night Clinton and his entourage, George Stephanopoulos and Bruce Lindsey, returned to Little Rock in a small private jet from all-important New Hampshire. I met the plane on the dark, deserted tarmac to give Clinton his next day’s schedule. He descended the jet’s stairs with a big smile, came directly at me, grabbed my coat and ran his hands up and down my long furry lapels. “Nice coat, Regan,” he whispered.

1991 I abruptly left Chicago for Arkansas to work as Clinton’s campaign scheduler, a grueling job that required 24/7 attention. One cold January night Clinton and his entourage, George Stephanopoulos and Bruce Lindsey, returned to Little Rock in a small private jet from all-important New Hampshire. I met the plane on the dark, deserted tarmac to give Clinton his next day’s schedule. He descended the jet’s stairs with a big smile, came directly at me, grabbed my coat and ran his hands up and down my long furry lapels. “Nice coat, Regan,” he whispered.