The all-white ceiling, walls, sheets and blankets, sealed the room in purity. My pain-free body, surrounded by downy pillows, laid on a pressure-sensitive mattress. A wall of windows showed off the unobstructed Chicago skyline three miles away.

I had a new knee.

“Ceramic,” said the surgeon, “like Corning Ware.”

The nurse floated in, smiled, said my name and schooled me on the morphine drip. She set graham crackers and apple juice ever so carefully on my shiny spic-and-span tray, showed me how to operate the TV, and placed my phone within reach.

“Did my doctor put me on the VIP floor?” I asked.

“Oh no,” she laughed. “This is the floor for all the orthopedic patients. You just lucked out with the view.”

The midday sun laid itself down on the city, my city, silhouetting the Sears Tower and the John Hancock Building. I drifted in and out as Lake Michigan peeked into the downtown streets and into my outstretched heart. Such joy. Comfort. Bliss. The phone vibrated at my fingertips, jiggling me awake.

“Hello? Regan? This is Joe.”

Ah, my son. He’s calling to ask how I’m doing.

“I hate bothering you like this. I’m in the hospital with my Dad. I don’t think he’s gonna make it.”

I’d been divorced from Jim, the only man I ever loved, for about 45 years. We’d met in a Jersey Shore bar in the 1960’s. I lived and breathed politics. He was on scholarship at Princeton and was the first boy I knew who read the same books I did. He proudly proclaimed himself a Democrat when the rest of us were simply anti-war.

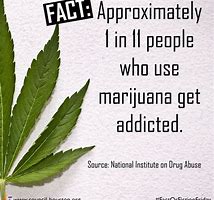

Lifeguarding in the summer, he loved the ocean, birds, rock-and-roll and beer. We were born for each other, but drinking and drugs destroyed our marriage. We divorced and I got help. Jim became helplessly addicted to marijuana. By the time he got help, his brain was fried. Between the irreversible brain damage and advanced diabetes, he could not survive on his own. Rather than house his father in a full-time care facility, Joe brought him to live with Joe and his family in a Chicago suburb.

I saw Jim once in a while—at Christmas, the grandchildren’s high school graduations, birthdays. He always recognized me and engaged in conversations about politics. Watching local news on TV all day left him thinking he lived and voted in Chicago.

“About the mayor’s race. Who should I vote for?” He asked. “I don’t like that guy Rahm.”

One last time Jim tried to shake off his dementia. He scheduled a cruise, making all the arrangements himself. Joe gave the ship’s nurse a detailed description of his father’s condition. She guaranteed his safety. But barely off the coast of Florida, Jim slipped into a coma and was airlifted to a Ft. Lauderdale hospital. He never recovered.

Joe and I talked until my painkillers wore off. Dusk overpowered the room. I banged the morphine pump, screamed for the nurse and wept for my long-ago lost love.

little crevices around the balcony door that were spritzing air into my not-so-insulated living room. That was the extent of my preparation for the coldest two days ever recorded in Chicago.

little crevices around the balcony door that were spritzing air into my not-so-insulated living room. That was the extent of my preparation for the coldest two days ever recorded in Chicago. place and stay still to conserve the calories heating their bodies. The weather should have kept the crows out of sight.

place and stay still to conserve the calories heating their bodies. The weather should have kept the crows out of sight.

movie theater to see “Vice” for the second time. Handsome, jovial cool cats at the Clark and Division bus stop grappled with grocery bags full of beer and pretzels. They were in mid conversation as they boarded:

movie theater to see “Vice” for the second time. Handsome, jovial cool cats at the Clark and Division bus stop grappled with grocery bags full of beer and pretzels. They were in mid conversation as they boarded:

“My god, a whole exhibit devoted to prostitution,” my companion whispered halfway around the showcased Japanese beauties.

“My god, a whole exhibit devoted to prostitution,” my companion whispered halfway around the showcased Japanese beauties. just like their human predecessors in the ancient world. I had not opened my low-slung coffee table drawers since my grandchildren stopped overnighting several years ago. I kept them in tact as a mini-shrine to time standing still.

just like their human predecessors in the ancient world. I had not opened my low-slung coffee table drawers since my grandchildren stopped overnighting several years ago. I kept them in tact as a mini-shrine to time standing still. in to help me, their old grandmother with her limited sense of place. Another would whisper, “pick the left one” knowing the hat on the left was empty. They thought juking me was hilarious. I did too, but for different reasons—my delight was simpler: I loved hearing them laugh.

in to help me, their old grandmother with her limited sense of place. Another would whisper, “pick the left one” knowing the hat on the left was empty. They thought juking me was hilarious. I did too, but for different reasons—my delight was simpler: I loved hearing them laugh.