At the Convent of the Sacred Heart in 1958, Mother Cleary announced at the weekly school assembly the name of the annual school play. She was uncharacteristically gleeful.

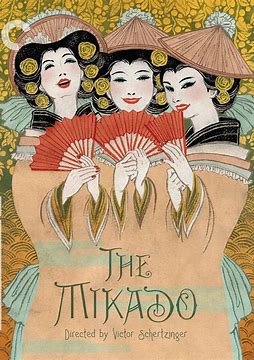

“Gilbert & Sullivan’s The Mikado will be this year’s play. We’ll start auditions next week. The entire school will take part. It will be a real pageant!”

The “convent” was a community of nuns and a Catholic girls’ school for grades five through twelve in a pastoral Chicago suburb. The nun’s surnames Riley, Doyle, O’Brien, and McCarthy would lead outsiders to think the order of the Religious of the Sacred Heart of Mary has its roots in Ireland. Not so. The order originated in France. Wealthy Irish families paid to have their well-educated daughters live and teach as “Madams” of the Sacred Heart, as they were known colloquially.

On hearing the news of The Mikado, we in the lower grades looked at each other with a shrugged Huh? The high schoolers cheered. Full of musicians, music lovers, budding drama queens, or future dramatists, the upper grades knew their Gilbert & Sullivan.

Gilbert & Sullivan wrote their 1885 comic opera as a satire on Victorian mores, culture, and government. The plot of The Mikado is the operatic old stand-by of an adolescent boy and girl trapped in forbidden love. The forbidden in this opera is a law against flirting. Some like to think Gilbert & Sullivan used the ridiculous plot to mock England’s law against homosexuality.

The late 1880s British society, the Victorian era, is known for its sexual prudishness. As an eighth-grader in the 1950s, I doubt I knew the word “Victorian” was synonymous with hypocritical sexual repression. Do you suppose those crafty Sacred Heart nuns were trying to get some subliminal point across to their mostly virginal students?

Those in the know at school aroused curious excitement about the play, the music, the staging, and the costumes. Oh, the costumes. The Mikado is a fake Japanese story, and the buzz about the songs, the kimonos, the make-up, and those hairdos filled my dreams with whirling color.

In Catholic schools, everyone sings in the choir throughout the year’s many feast days. When it came to my turn to audition, I had high hopes of landing a dramatic singing part. I had no idea I couldn’t carry a tune. My seventh-grade sister and I were called together to audition with Mother Cleary.

“Oh, girls, we have the perfect parts for you! You will be dressed as mackerels and stand as sentries on either side of the stage for the entire play! Isn’t that exciting? You’ll be visible the whole time!”

“Mackerels? You mean fish?” I asked.

“Yes, yes, yes! Don’t worry; you aren’t required to attend all the rehearsals—just the last few. Mother O’Brien will contact you about your costumes.”

“I won’t be singing?”

“Oh no, dear. That isn’t a part for you.”

“Thank you, Mother.” No matter how dispirited I felt, I knew manners were required. Pretending to be grateful was more virtuous than expressing true feelings.

Our costumes were colorful green felt tunics with blue and grey scales stitched in rows around the entire body. A fin and fishtail were sewn to the back, not that it mattered since only the front was visible on stage. I loved my costume. Mother O’Brien fitted it just right. But the fish head? It was a gigantic papier-mâché exaggeration of a mackerel head with slits for us to look out. We had to wiggle into our heads in the wings and be led to our spots at each edge of the stage. The smell of fresh white paste never dissipated inside the mackerel head.

We held silver staffs fastened to oversized cardboard hatchets. The mackerels were also executioners.

As executioner mackerels, we stood sentry throughout the play — a constant reminder to the audience that The Mikado is about death. Self-decapitation, being buried alive, and boiling in oil are all described in The Mikado as humorous ways to die if caught flirting. Death is funny.

I suppose for nuns cloistered in their habits, satire about death allowed them a fun escape from the reality of staring at a bleeding dead man on the cross at daily matins. My thoughts have turned to death every day before and since The Mikado because of that same bleeding dead man on the cross. But the play permitted me to laugh at death, and myself, for that matter.

As for Gilbert & Sullivan, I feel nauseous whenever I hear The Mikado’s “Pretty Little Maidens.” I suffer from a subconscious sixty-five-year-old humiliation that I buried while standing on that stage for hours, holding a weapon meant to decapitate.

Funny or not.

Thank God Erin wasn’t chosen to sign, that at least was a kindness!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah..am feeling a bit like your part in your Mackerel costume..being decapitated in this darkness.. Ya know… Denise

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hilarious comment. Thanks.

LikeLike

The fish role sounds terrible

LikeLiked by 1 person

I also, couldn’t hold a tune. For some reason the director always wanted me in his musicals and the music director wanted to cut me. It was a weird vibe. Now that I know how terrible a singer I am, I can’t figure it out at all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

hmmm. Maybe something sinister going on there with the director.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Could be. Maybe my singing was fine and the music director was just trying to protect me. 🤣

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for sharing. I saw Mikado presented as an opera at Illinois Wesleyan University. It was excellent and the music was engaging. I am sorry that you never got to sing as a mackerel fish. All of these experiences shape who we are today.

Peace and blessings, Donna

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Regan I did not have the Madames I would love to have seen you I had the School Sisters of Notre Dame A semi cloistered order

Oh those were the days

Love,

Ellen

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for sending I did not have the

LikeLike

Very clever. Nice take on wry humor. Peg

Sent from Mail for Windows

LikeLiked by 1 person