She came to me at nine years old with an incomplete backstory. No longer a viable breeder after age five or six, the owners kept her way past her financial contribution to the family. She’d delivered two litters a year, about 100 puppies. “We just liked her,” they told me. My inquiry, “I’m an old lady dog-lover, looking for an old-lady dog companion,” hit just the right tone. “You’re an answer to our prayers.” And so I got Elsa.

The day after the attempted assassination of the former president, I hungered for Sunday air. You know, the first day of the week kind of air, where everything starts over. Air that requires nothing. No lofty thoughts, no reflection, no opinions, judgments, or conclusions. Sunday air. I breathe Sunday air when singing a well-known hymn like “It is well with My Soul”.

When peace like a river, attendeth my way

When sorrows like sea billows roll

Whatever my lot

Thou hast taught me to say

It is well, it is well, with my soul

And when the preacher elevates my being with no effort on my part, I breathe in the Sunday air of love.

Sunday air was unattainable at church last week, though. It was not well with my soul. Right off, the preacher prayed “for former President Trump, grateful he did not succumb to political violence. This world is in love with violence, a violence that threatens the best in us, so renew in us a commitment to the Christ, who calls us to turn the other cheek, to love our neighbor, to love our enemies.” On receiving this, I sucked in a big chunk of we’re-gonna-lose and couldn’t seem to exhale.

The sermon choked off any puff of relief— a parable about prayer that meant nothing to me. My diaphragm would have swelled during hymn-singing, but the tunes were unfamiliar yawns.

And so, airless, I vamoosed to the outdoors, home to fetch Elsa for a trip to the park to watch tennis players sweat it out. She was too hot to sniff around the edges and lazed in the shade instead. Until a tennis ball bounced toward her behind the chain link fence. She bolted for it and dug into the wire to try to slay that green fuzzy rodent stunt double. She would have broken her teeth to get to it. A tennis player picked up the ball, a good ball, and tossed it over the fence with big Sunday air to Elsa, who received it with the gusto of a kid catching bubbles. She flaunted her prize using all the primal dog moves that delight dog-loving humans. I never knew she was a ball dog.

Echoing Bill Maher, Bulwark podcaster Tim Miller asked his spirit guide and Managing Editor, Sam Stein:

“Can I say Trump is the luckiest dog on the planet?”

“No! You can’t say that.”

“I can’t?” Asked Miler.

“No! It’s not lucky to be almost assassinated.” Said Stein.

But Elsa. She’s a lucky dog.

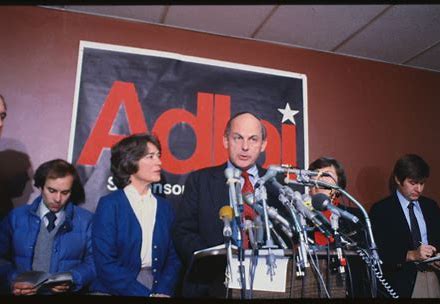

Adlai ordered another martini, a steak, baked potato and a salad. We ordered nothing. We had a lot of ground to cover, and food and drink would be in the way. When the second martini arrived, Adlai asked for beer with dinner.

Adlai ordered another martini, a steak, baked potato and a salad. We ordered nothing. We had a lot of ground to cover, and food and drink would be in the way. When the second martini arrived, Adlai asked for beer with dinner.

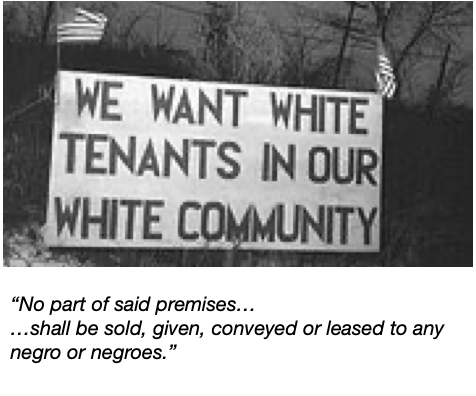

I hated money. When my father insisted I send my twelve-year old son to boarding school in the late seventies, I relented because I was afraid my father would stop paying our rent. My son resented me openly and I resented my father secretly. I’ve spent a lifetime declining requests from friends to join them in a subscription to the ballet or a share in a vacation beach house. Why? Money, that necessary evil that separates me from others.

I hated money. When my father insisted I send my twelve-year old son to boarding school in the late seventies, I relented because I was afraid my father would stop paying our rent. My son resented me openly and I resented my father secretly. I’ve spent a lifetime declining requests from friends to join them in a subscription to the ballet or a share in a vacation beach house. Why? Money, that necessary evil that separates me from others.