Waiting in examination room #5 for the skin doctor, I suddenly felt separated from the real world. Where was everyone? Was I in the right place? The right day? The right office? Where was I? Space stretched thin like over-rolled pie crust. I focused on deep breathing but knew I had to get out of there fast.

There’s nothing wrong with my skin. My mother called it “cheap Irish skin” because the sun burns it bright red, never a gold-plated tan. Splotches of actinic keratosis or “AK” from years of sun exposure periodically scale up on my face. The dermatologist unholsters an aerosol can from her belt and shoots liquid nitrogen on my AKs during twice-yearly visits. It creates instant frostbite on the dead cells, freezing the AKs in place. It doesn’t hurt. There’s no downside, no need for alarm and certainly no reason to have a panic attack.

“Anything else I need to look at?” the dermatologist asked.

No. This wasn’t the time for new concerns about my skin. I was on the verge of collapse.

By the time I got down the elevator into a lobby chair, hyperventilation was threatening to kill me. I thought I’d been in exam room #5 for a few hours but when I checked the time only thirty minutes had passed. Why were my legs so weak? I focused on my breathing until I recovered.

Looking for understanding, I later mentioned the discomfort to a friend, who happens to be a doctor.

“What did they do for you?”

“Nothing. I didn’t tell them.”

“What? Are you crazy? If your blood pressure spiked you could’ve had a heart attack.”

She didn’t understand. It was impossible for me to report my condition at the time. The pinched air sucked the words from my mouth. I couldn’t talk. I thought I was going crazy.

Panic attacks started in earnest a few years ago without any warning (not that I’d have recognized the warnings). I visited an old friend in the hamlet of Baltimore, a sailing community on the rugged southwest Irish coast. Vivienne and her friends were boarding a rubber inflatable one day for transport to a sailboat moored in Roaring Water Bay. She shouted “Get in!” as she crawled into the idling dinghy.

“I can’t!”

“Yes you can. Get in! Get in!”

“I can’t! I can’t!”

I yelled at her over the roar and hum of end-of-summer harbor noise.

“Go without me!”

I ran to the bait shop restroom, then dragged myself to a wind-slapped bench and recuperated under the shade of a wild fuchsia hedgerow.

Later Vivienne joined me on the deck of the waterfront cafe. “I panicked,” I said. She understood. Convenient word, panic.

Last year I panicked at different times in several US airports. There’s a simple solution to that—stay out of them. Now I face the unpredictability of panic striking at any moment and for no reason. I’ve considered revealing this malady to my friends in case I’m in their company if it happens again. I wouldn’t want anyone rushing me off to the emergency room because they don’t understand. But whenever I mentally rehearse the words, the room sways. I can hear the questions, “what are you afraid of?” and “why do you think this happens?”.

The difference between me and Henry the dog is that as the human animal, I’m able to understand my psychology and articulate that understanding to others. But the stigma of perceived weakness stills me into secrecy.

How would I know if Henry, the non-human animal, encounters panic attacks?

fluffy white dog on the third floor.

fluffy white dog on the third floor.

the wall and I’ve never had the inclination to do so. Neither can I bring myself to replace the broken dishwasher or stove.

the wall and I’ve never had the inclination to do so. Neither can I bring myself to replace the broken dishwasher or stove. Some visitors are afraid of the mosquito-borne West Nile Virus so they spray gobs of poisonous DEET all over themselves. I’m as afraid of West Nile as I am of getting hit by a bus. Bugs fly in. Bugs fly out. Mosquitoes, moths, flies, bees, wasps — they come in, take a look around and go out.

Some visitors are afraid of the mosquito-borne West Nile Virus so they spray gobs of poisonous DEET all over themselves. I’m as afraid of West Nile as I am of getting hit by a bus. Bugs fly in. Bugs fly out. Mosquitoes, moths, flies, bees, wasps — they come in, take a look around and go out.

gave him the opportunity to dig up our new backyard?

gave him the opportunity to dig up our new backyard? sparrows, chickadees and one squirrel that sat on a parallel branch, squeaking and shaking his tail, tormenting the dog.

sparrows, chickadees and one squirrel that sat on a parallel branch, squeaking and shaking his tail, tormenting the dog.

High-rise apartment buildings bookend each corner in Ozzy’s block of early 20th Century townhouses. At one corner, Gary the doorman entertains his Thompson Hotel guests by pop-flying Milk Bone dog treats for Ozzy to snatch in midair. Their RBI reaches 80% most days. Rounding the corner on Oak Street, Ozzy sniffs out bowls of treats laid down by strangers at the shops I think of as clothing museums – Dolce and Gabbana, Tom Ford, and Carolina Herrara.

High-rise apartment buildings bookend each corner in Ozzy’s block of early 20th Century townhouses. At one corner, Gary the doorman entertains his Thompson Hotel guests by pop-flying Milk Bone dog treats for Ozzy to snatch in midair. Their RBI reaches 80% most days. Rounding the corner on Oak Street, Ozzy sniffs out bowls of treats laid down by strangers at the shops I think of as clothing museums – Dolce and Gabbana, Tom Ford, and Carolina Herrara. caterpillar coat (easily seen in the dark), slip-proof gloves (for hanging onto the leash), cleated boots, Ozzy’s sweater, and dog boots to protect from the stinging salt. We trudged across Michigan Avenue to East Lake Shore Drive by the Drake Hotel. They continually shovel and salt a long stretch of pavement there. The wind blocked any possible noise from street traffic, and the snow muffled foot traffic. We marched down the street then back, across Michigan Avenue, into the dog entrance of our building, up the elevator and into the hallway of our apartment. I loosened and lowered my hood and looked down to find Ozzy’s iced-up chain collar melting on the carpet – but no Ozzy.

caterpillar coat (easily seen in the dark), slip-proof gloves (for hanging onto the leash), cleated boots, Ozzy’s sweater, and dog boots to protect from the stinging salt. We trudged across Michigan Avenue to East Lake Shore Drive by the Drake Hotel. They continually shovel and salt a long stretch of pavement there. The wind blocked any possible noise from street traffic, and the snow muffled foot traffic. We marched down the street then back, across Michigan Avenue, into the dog entrance of our building, up the elevator and into the hallway of our apartment. I loosened and lowered my hood and looked down to find Ozzy’s iced-up chain collar melting on the carpet – but no Ozzy.

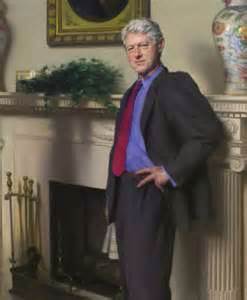

1991 I abruptly left Chicago for Arkansas to work as Clinton’s campaign scheduler, a grueling job that required 24/7 attention. One cold January night Clinton and his entourage, George Stephanopoulos and Bruce Lindsey, returned to Little Rock in a small private jet from all-important New Hampshire. I met the plane on the dark, deserted tarmac to give Clinton his next day’s schedule. He descended the jet’s stairs with a big smile, came directly at me, grabbed my coat and ran his hands up and down my long furry lapels. “Nice coat, Regan,” he whispered.

1991 I abruptly left Chicago for Arkansas to work as Clinton’s campaign scheduler, a grueling job that required 24/7 attention. One cold January night Clinton and his entourage, George Stephanopoulos and Bruce Lindsey, returned to Little Rock in a small private jet from all-important New Hampshire. I met the plane on the dark, deserted tarmac to give Clinton his next day’s schedule. He descended the jet’s stairs with a big smile, came directly at me, grabbed my coat and ran his hands up and down my long furry lapels. “Nice coat, Regan,” he whispered.