Standing in the driveway at 1000 Michigan Avenue in Wilmette, where we had lived for about a month, I posed with my tennis racket and ball while Erin snapped my picture with our family’s 1958 Kodak Brownie 127. We were playing in front of the garage doors on the west side of the house, an architectural oddity built into the side of the cliff overlooking Lake Michigan. The sun overhead lobbed burning sunbeams at my squinty-eyed face. Over my shoulder drooping into the curvy flagstone stairway leading down to our front door an overgrown lilac tree emitted a deep purple mid-June fragrance I’ve never forgotten. A robin strung together a complex trill from the upper branches of the evergreens that hugged the short driveway. My mother, not a naturalist in any sense of the word, somehow knew to teach Erin and me to recognize a robin’s song and the scent of lilacs.

We threw our rackets into our bike baskets, squeezed balls into the pockets of our Bermuda shorts and pedaled down red-bricked Michigan Avenue to our tennis lessons at

Gillson Park. Erin, a year younger, always aced her lessons and I always muddled through mine. We were both athletic enough but Erin outdid me in tennis. I was proud of her, and jealous.

Before heading home we rode over to Sheridan Road to the Bahia Temple. It had been open only a few years but neighborhood rumors said the big white Temple would soon be closed to the public. We laid our bikes in the greenish-blue lawn, climbed the white stairs and nonchalantly strolled around the outside. All the white doors were open but we saw no one. The stillness unnerved us. Holy. No chairs or pews sat in the white circular sanctuary. We pulled away from the white marble floor and creeped up three flights of white stairs to the white balcony. We peeked into the hush of the white holy. It was a long way down. I held a tennis ball over the white railing and looked at Erin. Her wide open face said,”let it go.” The ball fell into the white center of the sacred white floor. We froze. No one appeared. Then Erin dropped her tennis ball over the balcony. We crouched down and listened for the echoing plunk-a-plunk, then tore down the stairs and out to our bikes without looking back.

Halfway home we laughed so hard we fell into the thick grass by the side of the road. We got up and pedaled as fast as we could looking over our shoulders all the way home. We stashed our bikes in the garage as if they were evidence, and kept the secret between us until school started in the fall. Feeling invincible, we bragged about the tennis balls in the Temple to our classmates. Our crime, never exposed to adults-in-charge, fell into my ever-increasing life-bucket labeled “what I got away with.”

on his head within sight of all the bathers and sun worshipers around the pool. I sensed, in that instant, that this, my favorite spot in all Chicago, would be tainted for the rest of my life.

on his head within sight of all the bathers and sun worshipers around the pool. I sensed, in that instant, that this, my favorite spot in all Chicago, would be tainted for the rest of my life.

Stress Bay 3, injections shot my heart rate sky high, my breathing stretched to its outer limits, then it all parachuted back down. The whole test took ten minutes. I figured if I didn’t have a heart attack after that, God had absolved me of my lifelong mashed potatoes intake.

Stress Bay 3, injections shot my heart rate sky high, my breathing stretched to its outer limits, then it all parachuted back down. The whole test took ten minutes. I figured if I didn’t have a heart attack after that, God had absolved me of my lifelong mashed potatoes intake.

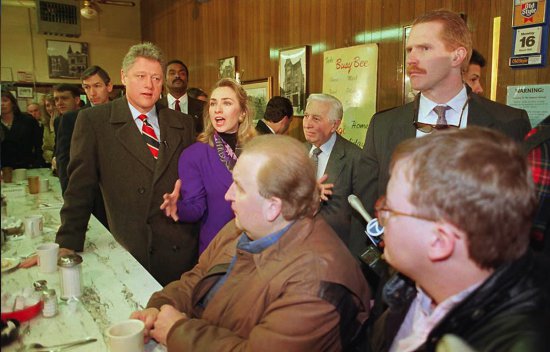

tall navy-suited body seemed to shift the atmosphere, moving the dust molecules away from him and clearing the air as he moved. He gave a hardy salutation and proceeded to introduce himself to each person while he circumnavigated the room, one-by-one. I was halfway around the table, and when he reached me I stood and looked up to his bemused rosy face, full of laugh lines. He had a big red nose, like Santa Claus. As I tried to introduce myself, he interrupted me by saying he knew who I was— the Executive Director of the state Democratic Party. He asked if I knew my name was the same as one of King Lear’s daughters. “Yes,” I said, “My name came from her.” He leaned over and whispered let’s keep that between us since she wasn’t such a great character. And just like that we had a best-buddies pact.

tall navy-suited body seemed to shift the atmosphere, moving the dust molecules away from him and clearing the air as he moved. He gave a hardy salutation and proceeded to introduce himself to each person while he circumnavigated the room, one-by-one. I was halfway around the table, and when he reached me I stood and looked up to his bemused rosy face, full of laugh lines. He had a big red nose, like Santa Claus. As I tried to introduce myself, he interrupted me by saying he knew who I was— the Executive Director of the state Democratic Party. He asked if I knew my name was the same as one of King Lear’s daughters. “Yes,” I said, “My name came from her.” He leaned over and whispered let’s keep that between us since she wasn’t such a great character. And just like that we had a best-buddies pact.