Most gay anthem playlists include these songs: I Will Survive by Gloria Gaynor, Freedom! ’90 by George Michael, Vogue by Madonna, I’m Coming Out by Diana Ross, anything by Beyonce, Cher, Donna Summers, Lady Gaga and of course, Billy Porter. But no recognition for the song Born Free.

I recently attended a friend’s bon voyage picnic with my new dog. 99% of the picnickers were men. They adored my fluffy little white Westie with her pink-lined pricked ears.

“What’s her name?” One guy asked.

“Elsa,” I answered.

He and his companion then broke out singing Born Free. Others joined in the serenade.

Born free, free as the wind blows…

I looked straight at my friend with a questioning side smile and squinty eyes.

“Gay,” was his answer.

“Some kind of anthem?” I asked.

“Yep. From the movie.”

“Oh, I get it. Elsa. The lioness. Wanna go with me & Elsa to the Pride parade?” I asked him.

“Absolutely not!” he exclaimed.

None of my gay friends express interest in Pride hoopla. At least not to me. But in social gatherings, I’ve overheard one or more talking about some cute guy they’d met at the Parade. It’s understandable. The Parade covers a lot of geography and seems to have no time constraints. If you live in Parade neighborhoods, you’re bound to meet a cute guy or two passing by.

The rejection of Pride celebrations is a bit more puzzling. I’m not particularly drawn to St. Patrick’s Day parties and parades, but neither am I celebrating Irish freedom. After the first official Chicago Pride parade in 1981, I celebrated gay liberation at a raucous party in Lincoln Park . Plenty of our gay friends were invited. But they didn’t show. Perhaps they excluded us from their Pride activities because gay liberation didn’t belong to us? Nor we to it?

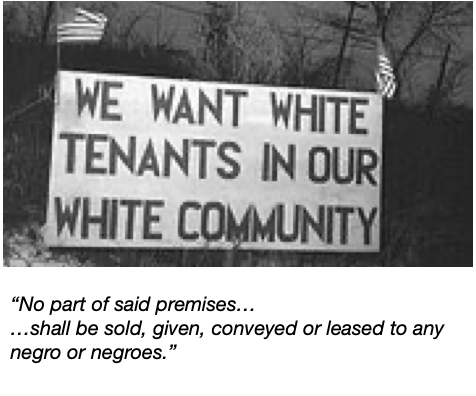

Political friends wave the flag, not necessarily to show they’re gay, but, as I do, to support gay rights. Showing the colors this year is especially important because recent laws in other states restrict gay freedom, including drag shows.

On a stroll down Michigan Avenue the other day, I was overwhelmed by the display of rainbow colors in front of my church. There are ribbons tied to each iron fence post spelling out the iconic colors of gay pride—for the entire block in front of the church.

“So colorful,” I mentioned to my walking companion.

“Doesn’t it make you feel kinda bad?” She asked.

“Whaddya mean?”

“Well, it’s a celebration for gays. And you’re not.”

Some of the church’s older adults asked to celebrate gay rights by having a drag show for their small group. The church denied the request. I’m excluded from men’s bible study, twenty-somethings and couples church groups. And like those, perhaps celebrating gay freedom with events like drag shows, really is (inadvertently) reserved for gays only.

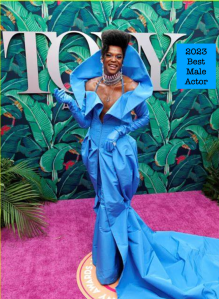

Fortunately, I can honor the entire queer nation by re-watching this year’s Tony Awards.

Meanwhile, song compilers need to include Born Free in gay anthem song lists.