James Carville called in early March 1992.

“This is not your fault,” he said in that red-hot Cajun voice of his, ”I take full responsibility.”

I knew right then that the campaign advisors on the road with Bill Clinton were blaming me.

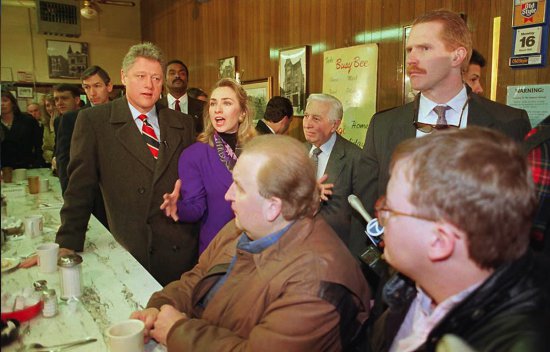

A few days earlier, Carville, chief strategist for the campaign, had directed me to schedule Clinton at a correctional facility in Georgia reasoning that a picture of Clinton strolling with black inmates and Georgia’s all-white male politicians would cinch Clinton’s appeal to the state’s voters.

It did.

Clinton won the Georgia primary, but not without a price. The national press and the other candidates excoriated Clinton for his racial insensitivity. Jerry Brown said Clinton and the other politicians looked “like colonial masters” trying to tell white voters “Don’t worry, we’ll keep them in their place.”

And that was all my fault.

Five months earlier I’d been asked to give up my job in Chicago and relocate to Little Rock to be Clinton’s Director of Scheduling and Advance. “You already know this, Regan,” Campaign Manager David Wilhelm reminded me, “the scheduler in any campaign has the worst job.”

It’s true. The person who plans the candidate’s calendar has an enviable yet risky position. An unplanned photo with an unscrupulous politician? Protesters blocking the entrance to an event? A rained out rally? It’s all the scheduler’s fault.

Campaign operations temporarily moved from Little Rock to the Palmer House in Chicago just before the Illinois-Michigan primaries in 1992. The extensive Chicago staff in Little Rock wanted to celebrate Clinton’s St. Patrick’s Day victories that would clinch

the nomination.

An old friend of mine, a Chicago policeman, volunteered to be Clinton’s driver. He called me around 2:00 am the morning before the Primary.

“Regan, that Greek guy, George, and Bruce someone were in the car telling Clinton you have to go.”

“What?”

“Yep. But Clinton said he wants to be sure you have another high-level job in the campaign.”

“Really?”

“Yeah! Dees guys are strategists? Der talkin’ ‘bout firin’ you in your hometown — and your buddy drivin’?”

We howled at the strategic error.

I was offered a job that was already filled. Wilhelm shrugged when I asked if I was fired. The New York Times reported I’d been replaced by Bruce’s wife.

I took a trip to the Bahamas, became achingly lonely and came home early. Herb and Vivienne Sirott got me into a rental apartment across the hall from them. Cook County Clerk David Orr hired me as Deputy Director of Elections. We worked hard that year to pass the National Motor Voter Act. A young community organizer, Barack Obama, walked into my office to plan a large-scale voter registration project.

Things looked good from the outside, but inside ego-busting despair maintained constant watch over my soul. Depression, sick leave, isolation, shame, all led to suicidal thoughts. Vivienne brought a psychiatrist to my apartment. That’s when I started Prozac, my first legal anti-depressant.

tall navy-suited body seemed to shift the atmosphere, moving the dust molecules away from him and clearing the air as he moved. He gave a hardy salutation and proceeded to introduce himself to each person while he circumnavigated the room, one-by-one. I was halfway around the table, and when he reached me I stood and looked up to his bemused rosy face, full of laugh lines. He had a big red nose, like Santa Claus. As I tried to introduce myself, he interrupted me by saying he knew who I was— the Executive Director of the state Democratic Party. He asked if I knew my name was the same as one of King Lear’s daughters. “Yes,” I said, “My name came from her.” He leaned over and whispered let’s keep that between us since she wasn’t such a great character. And just like that we had a best-buddies pact.

tall navy-suited body seemed to shift the atmosphere, moving the dust molecules away from him and clearing the air as he moved. He gave a hardy salutation and proceeded to introduce himself to each person while he circumnavigated the room, one-by-one. I was halfway around the table, and when he reached me I stood and looked up to his bemused rosy face, full of laugh lines. He had a big red nose, like Santa Claus. As I tried to introduce myself, he interrupted me by saying he knew who I was— the Executive Director of the state Democratic Party. He asked if I knew my name was the same as one of King Lear’s daughters. “Yes,” I said, “My name came from her.” He leaned over and whispered let’s keep that between us since she wasn’t such a great character. And just like that we had a best-buddies pact.

commandments to week-old smiles, cries in the night, a nine-month old sprinter and a child who eats only chicken. My work is to stand my ground in the whirlwind advice from mothers, aunts and grandmothers. To learn to ride a baby on the back of my bicycle. To animate words as I point to clouds, trees and cars as if I’ve never seen these things before in my life.

commandments to week-old smiles, cries in the night, a nine-month old sprinter and a child who eats only chicken. My work is to stand my ground in the whirlwind advice from mothers, aunts and grandmothers. To learn to ride a baby on the back of my bicycle. To animate words as I point to clouds, trees and cars as if I’ve never seen these things before in my life.

1991 I abruptly left Chicago for Arkansas to work as Clinton’s campaign scheduler, a grueling job that required 24/7 attention. One cold January night Clinton and his entourage, George Stephanopoulos and Bruce Lindsey, returned to Little Rock in a small private jet from all-important New Hampshire. I met the plane on the dark, deserted tarmac to give Clinton his next day’s schedule. He descended the jet’s stairs with a big smile, came directly at me, grabbed my coat and ran his hands up and down my long furry lapels. “Nice coat, Regan,” he whispered.

1991 I abruptly left Chicago for Arkansas to work as Clinton’s campaign scheduler, a grueling job that required 24/7 attention. One cold January night Clinton and his entourage, George Stephanopoulos and Bruce Lindsey, returned to Little Rock in a small private jet from all-important New Hampshire. I met the plane on the dark, deserted tarmac to give Clinton his next day’s schedule. He descended the jet’s stairs with a big smile, came directly at me, grabbed my coat and ran his hands up and down my long furry lapels. “Nice coat, Regan,” he whispered.