The radio. How I love the radio!

Transistor radios first appeared on the shelf behind the cashier at Walgreen’s, alongside the cigarettes, in the 1950s. The purchase price was cheap enough for my mother. I can’t imagine what my life would have been had it not been for the radio.

In our teens, we lay on the floor, smoking pot and singing to the Beatles on the radio. A friend once mused, “our lives would be more manageable if it weren’t for the radio.” Every half hour DJs stopped spinning records and announced the news. Radio news. It stirred me up for life.

The radio these days is an Amazon Echo. It is set to turn on NPR at 7:00 am in my house these days. On Sundays, I usually ignore a 7:00 am show called Hidden Brain. A neuroscientist interviews interesting enough people, but I just want to hear the news at 8. Recently I put off walking the dog and making coffee when I heard the voice of Dr. James Pennebaker on Hidden Brain. He talked about how people’s language, written and vocal, signals what’s happening inside their heads.

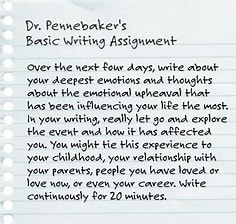

James Pennebaker is a social psychologist at the University of Texas-Austin. He taught me that chronic pain can be healed through expressive writing. His recipe, grounded in scientific research, consists of writing it down. Just write it down. It’s cheap, easy. And it works. My writing teacher Beth Finke and I used to call it bibliotherapy. Pennebaker’s books are sweet old friends. The same goes for Jon Kabat-Zinn’s Full Catastrophe Living, John Sarno’s Healing Back Pain, and Howard Schubiner’s Unlearn Your Pain. Thinking of these now butters my memory with gratitude. I write because these authors taught me words can heal. And, for the most part, they have.

I’m not particularly interested in interpreting the language of my friends. I don’t want to know what’s happening in their noggins as Pennebaker does with his research subjects. No, what’s tasty lately about Pennebaker is what he says about Donald Trump.

He examined Trump interviews from 2015 to 2024 and found a whopping 44% increase in words plated in the past. What’s that mean? Well, usually presidential candidates dish out rhetoric about the future. Pennebaker says Trump whips up such simple words and sentences that he can only be described as “an incredibly simplistic thinker.”

“I can’t tell you how staggering this is,” he told Stat News. “He does not think in a complex way at all.”

I loved hearing this. And there I was again, glomming on to any tidbit that humiliates and demeans Trump. It’s called schadenfreude. I love that word but ashamed how I delight in its meaning: the experience of pleasure, joy, or self-satisfaction that comes from learning of or witnessing the troubles, failures, pain, suffering, or humiliation of another.”

Schadenfreude is one of the delicious habits I metabolized, after using Pennebaker’s and others’ writing exercises to relieve chronic pain. Obviously this is not a vice easily kept at bay. Availing myself of some form of spirituality, like meditation, helps. And the writing, of course.

But for now, it’s back to the radio.