At the Goodman Theater Chicago’s Storytelling class, teaching artist Julie Ganey prompted us to write a “story of changed perspective” based on Goodman’s production of Margaret Atwood’s Penelopiad.

I had a story in the can, Lunch Money, about a changed perspective, and decided to revise it for the storytelling assignment before I saw the Penelopiad performance. When I finally saw Peneliopiad, I couldn’t see the change in perspective theme—still can’t. Did Penelope change her perspective? Did Odysseus? Who? What?

Had I seen Peneiopiad first (one of the best productions I’ve ever seen in any theater anywhere), I would have written about an experience in honest storytelling. I have lots of those. But, alas, it’s best I don’t sermonize on truthtelling. The following is my change-in-perspective story, which I’ll soon be reciting in person at the Goodman Theater’s “Lobby Stories.” If you’re a regular blog reader, thank you; you’ll understand why retelling this story is important.

Lunch Money Reparations

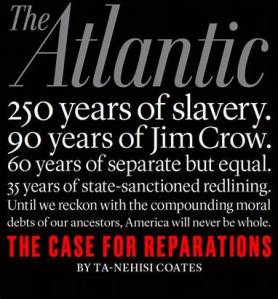

Reparations are a program of acknowledgment, redress, and closure for a grievous injustice. — From Here to Equality, Reparations for Black Americans in the 21st Century, by William A. Darity, Jr. and A. Kirsten Mullen

When I started working as a part-time receptionist in downtown Chicago, I lived with my nine-year-old son in a high-rise apartment and periodically spent more money than I had. Glitzy earrings or a new red lipstick often called to me as I passed through Marshall Field and Company on State Street. I once had my entire purse stolen off the counter as I adjusted my scarf in the mirror.

When I started working as a part-time receptionist in downtown Chicago, I lived with my nine-year-old son in a high-rise apartment and periodically spent more money than I had. Glitzy earrings or a new red lipstick often called to me as I passed through Marshall Field and Company on State Street. I once had my entire purse stolen off the counter as I adjusted my scarf in the mirror.

Over the years, I’ve faced down quite a few street scams and purse snatchings. The worst was the time three teenage boys trapped me in a revolving door at the old Carson, Pirie Scott building. One had yanked on my purse as I entered, but I grabbed the shoulder straps while the accomplice pushed the door in the section in front of me. The accomplice stopped abruptly and held his hands on both glass doors. This left each of us stuck in a different section of the revolving door, awkwardly staring at each other through the glass. They all ran off when a security guard came to my rescue.

I added this grievance story to others like it. Joining the ranks of privileged pseudo-traumatized victims, I loudly condemned an exaggerated version of the bands of criminals marauding downtown Chicago.

As a pensioner, I’ve inoculated myself against criminal assault by carrying nothing but my iPhone and a pocket-size purse where my bus pass, credit cards, and a small amount of cash are stored. Costume jewelry and cosmetics are no longer a retail draw. But I cannot resist accepting Dutch treat lunch invitations from friends, paying no attention to my budget or bank balance.

One day, I sat waiting for a fellow retiree, Peter McLennon, in the lobby of a busy hotel where we’d planned to have lunch. I delved into my ever-present iPhone with heightened curiosity to see if anything big had happened between the time I had gotten off the bus, walked the two blocks to the hotel lobby, and plopped down in the overstuffed chair.

I was so engrossed in the breaking news of a car accident on a distant highway that my senses were dulled to a body stirring in the chair next to me. When the body started in on her story, I momentarily jolted to attention.

“My husband beat me for the last time. I been hidin’ in a women’s shelter but he found me, and now I need to move.”

“What?” I said as much to her as to myself since I was not quite tuned into her voice, my mind drifting in and out of her story while half-wondering what happened to the people in the car crash that was reporting out of my phone behind the now blank screen.

“My social worker found a place in Cincinnati. They gonna hold a room 24 hours. I need $19 for the bus. Can you lend it to me?”

“What?” I looked around to see if Peter was nearby to rescue me.

She repeated her story, adding some details about injuries inflicted by the husband.

“As soon as I get situated in Cincinnati with a place to stay and a job, I’ll pay you back.”

I tested her by asking if she was taking the mega-bus since $19 didn’t seem like enough money for a bus to Cincinnati. That stumped her, but she recovered nicely by describing where the bus station was.

And for one shimmering split second, we caught each other’s eyes and I sensed she knew I was on to her. But she kept up the hustle. I admired that. She was working hard for her money.

I unzipped my little red purse and happily handed her my $20 lunch money. Before I zipped up, she was gone. The scam worked. Relief washed over me as I exhaled the stress of her desperation. Even if I doubted her, she deserved all the money I had for all the years I’d spent harboring both silent and noisy racial bias.

When Peter arrived, he commented on how serene I looked. As we walked toward the restaurant, I asked if he could pick up the tab for lunch.

“Yes, of course.” He said.

And I didn’t even have to tell the story.