By the time I’d left the eighth grade, I’d attended thirteen schools. Dealing with all those changes led to the development of uncanny protean skills, including the art of answering questions before they were asked. For instance, my mother, Agnes, an ace at avoiding small talk, taught me:

“When you meet new people say, ‘My name is Regan. It’s from Shakespeare and it means queen in Gaelic’, so you won’t have to answer all their questions.”

This tactic thwarted the name questions on the first day of any new school, especially since my grade school classmates didn’t know what the heck I was talking about.

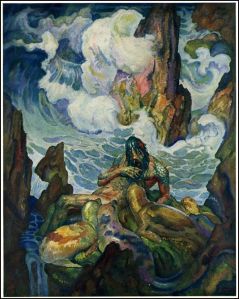

Word Daily, coughed up “protean” the other day, a word seen once in every 16,000 pages you might read. I never use it, though I completely click with the namesake origin, Proteus. He was a Greek sea god who knew all things, past, present, and future. Recognized as a shepherd of sea creatures, he slept among the seals and otters, which, save for the smell, appeals to the phantasms leftover from my childhood mermaid dreams.

Proteus escaped those seeking his knowledge by changing his shape to avoid answering questions. In modern parlance, not a shape-shifter, but rather someone flexible and adaptable, is protean.

In the lower grades, adapting to mean-girl culture, I inevitably and reluctantly had to announce, “I repeated first grade because I was sick; then I skipped second grade.” This answered the question of why I couldn’t add or subtract. If I had remained in that first-grade school, my parenthetical nickname would have been “The Repeat” all the way to the eighth grade. The Repeats were few but well-known. We bonded with knowing glances passing silently in the hallways.

We were Catholics. My sisters and I attended parish schools, wore parish uniforms. There was never a back-to-school ritual in our house because we never went back to a school we had been to before. The beginning of each new school year was a fresh start.

In Terre Haute we rode our bikes; in St. Louis the school bus. In downtown Indianapolis, we caught a public bus crammed with garlic-breathed commuters. In the Chicago suburbs, a school bus, my mother’s station wagon, bicycles, and walking, all brought us each year to a new building, a new neighborhood.

I never learned how to predict the future like Proteus (though a spiritualist on LSD once told me I had the gift of prophecy). Predicting what the next parish would be was never in the cards—it was always a mystery. My ears didn’t reach high enough to hear my parents deliberating the matter. But I could easily predict we’d be in a different school for the next grade. For better or worse, we all exhibited protean traits: flexible and adaptable.

Early on, knowing stuff came to be my raison d’être. I became and remain an insufferable know-it-all. Geographic stability has diminished the necessity for protean mental agility of late.

But protean knowledge? It continues to inoculate me from ever being called any version of “The Repeat”.