Every spring at Walsingham Academy, Sister Walter Mary selected a few students to prepare Catholic children for their First Holy Communion. The children were patients at the local mental institution, Eastern State Hospital in Williamsburg, Virginia. I have no idea why there were young children locked up in an insane asylum. We were trained to teach these pre-Ritalin six-, seven-, and eight-year-olds to memorize answers to preposterous questions such as “Why did God make me?” from the Baltimore Catechism.

It was pre-HIPPA 1963. We received basic training in mental illness. A hospital attendant walked us teenage tutors through the children’s wards, pointing out caged paranoid schizophrenics, psychopaths, and catatonics in their soiled grey tunics. Some children sprang at the chain-link fences, grabbing us and screaming obscenities. We didn’t teach this group. Our students lived in cozy dormitories and wore regular clothes.

Eastern State—the oldest psychiatric facility in the country—had been founded on the forward-thinking concept that insanity was an emotional disorder, not an aberrant behavioral condition. Treatment included exercise and social activities. Catholic parents treasured the outside instruction their little ones received. I’m not sure how much my first-grader learned because all she wanted to do was sit next to me and play with my hair. I helped her into her white veil and gloves and took her to nearby St. Bede’s, where she made her First Holy Communion with the local children. I met her parents at the church. I never saw them again, never learned her diagnosis, or if she ever left the institution.

A few years later, I worked an overnight shift at the Point Pleasant Nursing Home in New Jersey. My job was to straighten up—put games like Monopoly, bingo, and chess in their boxes and wiggle them into overstuffed cabinets. I wrote down missing pieces of each game so the next shift could look for them in patients’ hiding spots—pockets, drawers, purses.

A completed jigsaw puzzle of an Impressionist painting lay on its box cover under a window. I put the pieces back in the box and stuffed them into the cabinet with art supplies, books, and magazines. Before my shift ended, a patient wandered into the day room. She stopped at the space where the completed jigsaw had been and looked at me, panic-stricken. She grabbed my hair in a flash, shrieked I stole her art, and smacked me in the face. By the time the nurse reached us, we were both screaming.

In dementia, my mother, Agnes, carried an ever-present small clutch purse. At that same nursing home, the nurses gave her their old lipsticks because the click-clacking sound as she rifled in her bag calmed her down.

The day she died, I visited the nursing home and thanked the staff for giving my mother what I couldn’t: a proper confinement of love and respect to keep her from wandering around and terrifying her fellow creatures. Only then did I ache for the parents of the Eastern State girl I’d met twenty-five years earlier.

antique mahogany side table, and the other hand holding the grooved white plastic top, she’d drag the brush along the lip of the bottle to get just the right amount of polish. Pulling the brush from the bottom of the nail to the top in perfect form nail after nail, she’d quietly finish the job, then blow on the tips of her fingers to dry them.

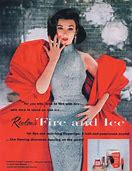

antique mahogany side table, and the other hand holding the grooved white plastic top, she’d drag the brush along the lip of the bottle to get just the right amount of polish. Pulling the brush from the bottom of the nail to the top in perfect form nail after nail, she’d quietly finish the job, then blow on the tips of her fingers to dry them. For a few years after my mother died, I entered into the ritualized glamor of painting my own nails red. I sat before a young manicurist who updated me every week on the intrigue of her affair with a rich married man. When she moved in with him and quit her job, the allure of painting my nails lost its luster.

For a few years after my mother died, I entered into the ritualized glamor of painting my own nails red. I sat before a young manicurist who updated me every week on the intrigue of her affair with a rich married man. When she moved in with him and quit her job, the allure of painting my nails lost its luster.