Guest Blogger Fritz Edelstein, Principal at Public Private Action, was the Director of Constituent Services in the U.S. Department of Education where we became friends during the Bill Clinton administration. Fritz lives in Park City, Utah, and for many years he produced the “Fritzwire” newsletter.

Let it Be by Fritz Edelstein:

“Let It Be,” one of The Beatles’ most iconic songs, is often seen as a poignant farewell to the band’s incredible journey. Written by Paul McCartney, it was released as a single in 1970 and became the title track of their final studio album. The song carries a timeless message of hope, resilience, and acceptance, making it a beacon of comfort for listeners across generations.

Moved by the dream, McCartney turned his feelings into music. The lyrics reflect his mother’s comforting presence, with lines like “When I find myself in times of trouble, Mother Mary comes to me, speaking words of wisdom: Let it be.”While some interpreted the song as having religious undertones, McCartney clarified that “Mother Mary” referred to his own mother, whose memory brought him peace during a difficult time.

Musically, “Let It Be” is both simple and profound. The gentle piano melody and soulful vocal delivery create a sense of serenity, while the gospel-inspired arrangement adds emotional depth. The song’s climactic guitar solo, played by George Harrison, gives it a stirring, cathartic energy. This combination of elements underscores the song’s universal message: even in times of uncertainty, there is solace in acceptance and hope.

The release of “Let It Be” coincided with the official breakup of The Beatles, giving the song additional weight. For fans, it felt like a farewell gift from the band—a reminder to cherish the good moments and embrace change with grace. The song’s themes of resilience and faith resonated deeply, particularly during the social and political upheavals of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Over the years, “Let It Be” has become a cultural touchstone, often played during moments of collective reflection or mourning. Its message transcends its origins, offering comfort in times of personal or global crises. For McCartney, the song remains one of his most personal creations, rooted in the memory of his mother’s wisdom and love.

As The Beatles’ final single before their disbandment, “Let It Be” serves as both a farewell and a timeless message of hope. It reminds us that even in the face of loss or uncertainty, there is peace to be found in letting go and trusting the passage of time.

___________________________

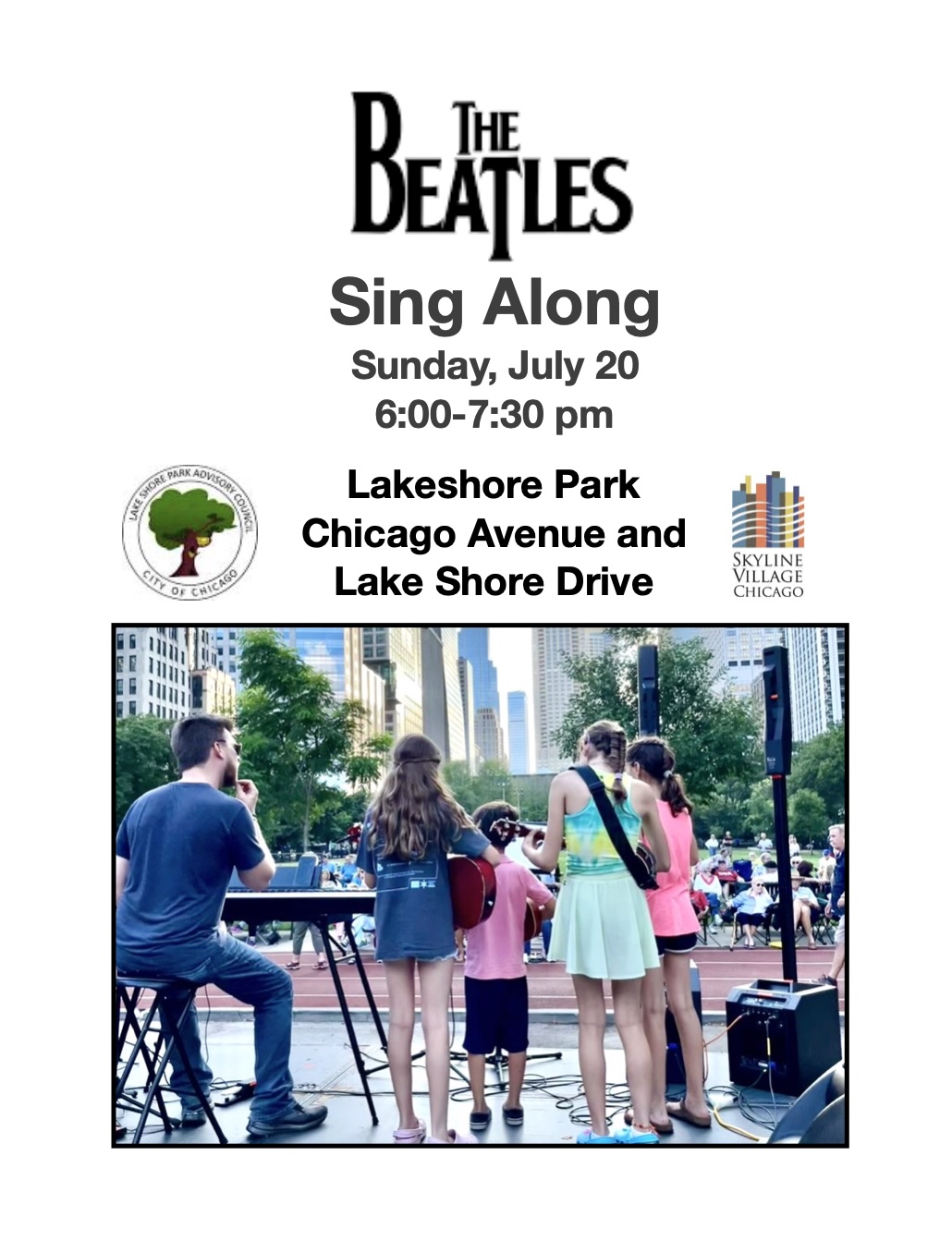

Join us in Chicago on July 20 to sing ‘Let it Be’ and 17 other Beatles tunes. It’s always the best event of the summer.