The Day of the Dead Mexican holiday, observed on November 1st celebrates the deceased with ofrendas (home altars) and festive gravesite visits. Tombstone gatherings include offerings of the deceased’s favorite food, drink, and music.

When I learned about my sister Mara’s death last spring, I reflected on our estranged relationship in a blog post. Since then, I’ve received a slew of messages from her friends that piece together a life I never knew, stories that give life to the dead.

Borrowing from the Mexican tradition, I offer an ofrenda to my older sister Mara Burke, with a sampling of those messages.

…we double-dated, attended formals at The Peddie School, and listened to music we loved. Her shop, where she helped us look stunning, but never as stunning as she looked, was where she generously gave us all our first credit cards! The slim silver bracelet she gave me many years ago is still my favorite, the many articles she sent knowing I loved cooking and gardening, and the tiny blue and white dish on my nightstand are fond remembrances of her love.

…I met Mara at the Catholic Home for Unwed Mothers.

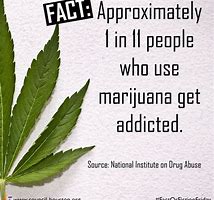

…I interviewed Mara for a job a few years after her store closed in the early 90s. She was a talented clothier, but she showed up smelling of booze.

…Mara was on my mind, i Googled her, saddened by the news i now read. I am happy to say that even though Mara and I were not close, we shared plenty of sobriety, laughter, and lots of very good coffee and pastry over the past 33 years.

… I met her in the 90s. We did a lot of meetings and healing through friendship with other recovering folks. She moved from Florida, and we lost touch.

…Mara came to care for me when I lost my mother years ago in a horrific accident. She has been through much with me and was selfless in her caring when my son died suddenly. My pain was her pain, and it was real.

…she always showed up for work even when she couldn’t stand up straight because of that hump on her back. She’s the best salesperson I’ve ever had.

… she was my neighbor for seven years. I set her up on a senior dating site. We laughed about all her dates. She never drank anything but coffee & ice water, attended Mass down the street and knew the priest. She said many times she wanted her ashes spread around her mother’s grave.

…she had that beautiful speaking voice.

… we had a beautiful day to carry out Mara’s wishes. We buried a small crystal heart dish Mara had given me with her ashes. We planted daffodil bulbs to bloom in the spring, said a prayer, and sprinkled her ashes over her mother’s grave.

Mara moved from Florida to Virginia for inexplicable reasons. Two weeks passed before her body was found on the floor of her apartment, and another week before I was called. The death certificate says she died of natural causes complicated by dementia and follicular lymphoma.

RIP, Mara Burke. Born February 14, 1945, died March 13, 2023.

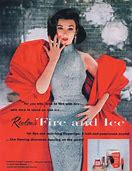

antique mahogany side table, and the other hand holding the grooved white plastic top, she’d drag the brush along the lip of the bottle to get just the right amount of polish. Pulling the brush from the bottom of the nail to the top in perfect form nail after nail, she’d quietly finish the job, then blow on the tips of her fingers to dry them.

antique mahogany side table, and the other hand holding the grooved white plastic top, she’d drag the brush along the lip of the bottle to get just the right amount of polish. Pulling the brush from the bottom of the nail to the top in perfect form nail after nail, she’d quietly finish the job, then blow on the tips of her fingers to dry them. For a few years after my mother died, I entered into the ritualized glamor of painting my own nails red. I sat before a young manicurist who updated me every week on the intrigue of her affair with a rich married man. When she moved in with him and quit her job, the allure of painting my nails lost its luster.

For a few years after my mother died, I entered into the ritualized glamor of painting my own nails red. I sat before a young manicurist who updated me every week on the intrigue of her affair with a rich married man. When she moved in with him and quit her job, the allure of painting my nails lost its luster.

My favorite place is anywhere there are trees.

My favorite place is anywhere there are trees.