Candles, Israel-Gaza, and a World We Don’t Have Yet

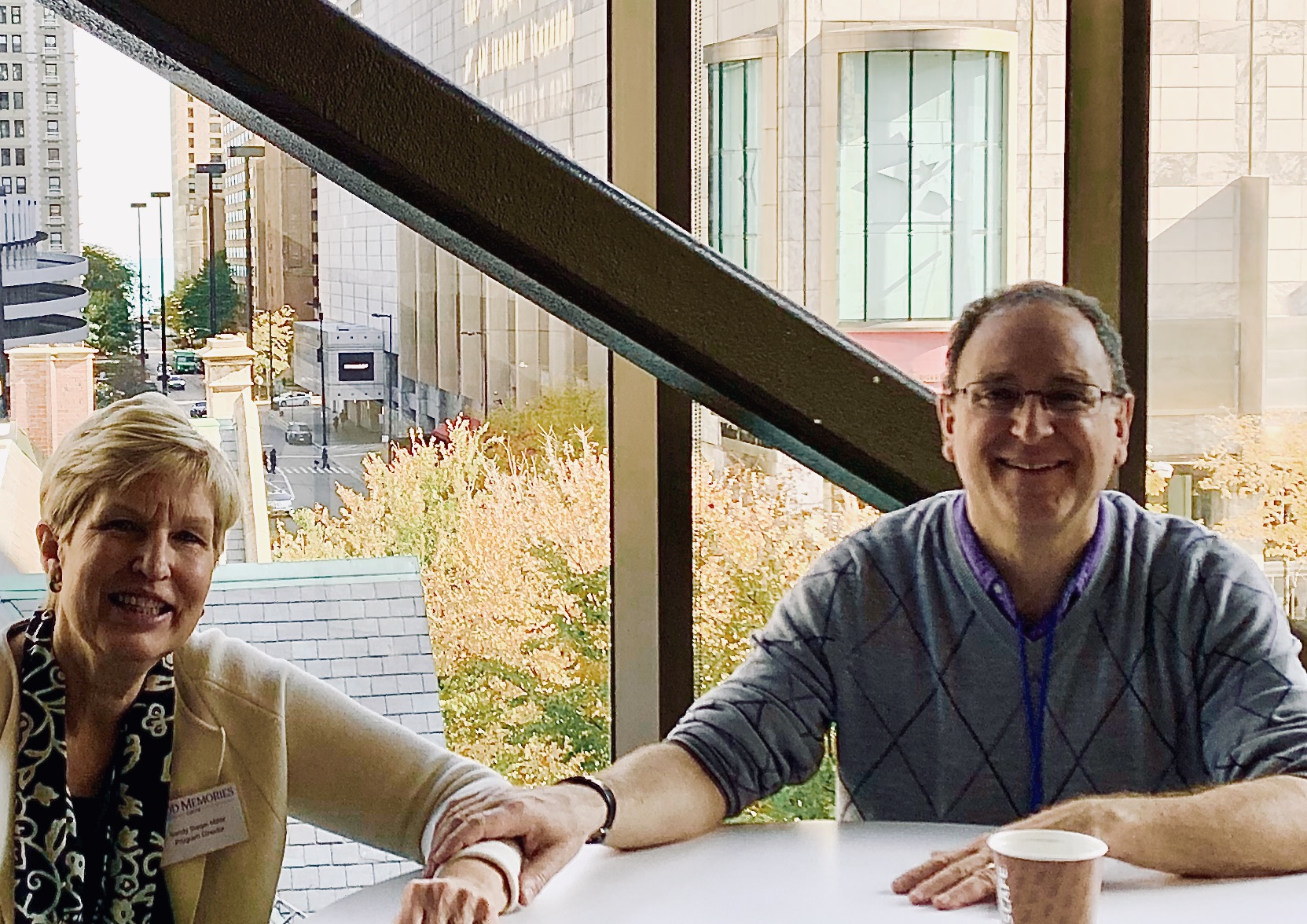

Jonathan and Sandy Miller founded “Sounds Good” choirs for older Chicago adults in 2016. Two years later, they added “Good Memories” choirs for those with dementia and early-stage Alzheimer’s. Having no background in singing and an inability to carry a tune or read music, I hesitated to volunteer to help people with following their sheet music. But Sandy and Jonathan said a fuller group would give people a better choir experience. So I joined.

I’d been worried that I had slid into a period of ever-increasing cognitive decline myself. In researching what was happening to me, I’d read that singing, particularly choir singing, could help stitch together busted nerve endings in the brain. It has. Learning to match the notes to the words, concentrating on reading the music, and trying to vocalize it seems to replenish bits of lost grey matter. Choir singing enlarges my world by healing the brain.

Little did I know that the world of Jonathan and Sandy Miller is a body, mind, and soul experience. The following essay was posted on the Sounds Good website. Jonathan Miller doesn’t “preach’” as our choirmaster. But he and Sandy exemplify every good quality expressed here.

Come hear the fruits of these labors at our concert in Chicago on Dec. 21, 2:00 pm, 4th Presbyterian Church, 880 N. Michigan Ave.

Candles, Israel-Gaza, and a World We Don’t Have Yet

by Jonathan Miller

We have been rehearsing “Light One Candle” in all of the Sounds Good Choirs for many weeks. When Linda Powell and I picked the song for this fall’s concerts, we had no idea how timely it would seem now—almost prophetic. It suddenly feels deeply relevant, especially when seen in the context of events unfolding in Israel and Gaza. What is happening there horrifies me as a Jew and breaks my heart as a human being. My heart cries out at the suffering that has taken place and is bracing for yet more suffering to come.

Look anywhere in your news feed for thirty seconds, and you’ll see it: we have not learned how to live together. A song, therefore, that acknowledges pain and suffering is a good thing right now. A song about “the terrible sacrifice justice and freedom demand” is a wise and timely song.

Light one candle for the Maccabee children

With thanks that their light didn’t die

Light one candle for the pain they endured

When their right to exist was denied

Peter Yarrow wrote “Light One Candle” in 1982 when war broke out between Lebanon and Israel; he said that he hoped the song would take hold in people’s hearts like “Blowin’ in the Wind” had captured American hearts during the Vietnam War. The song holds up the example of the “Maccabee children”—those Jews who stood up for themselves when the Romans took over the Temple in Jerusalem around 165 BCE—as a source of inspiration, resistance, and courage.

History gives us many such role models of courage. Sandy and I recently went to a fundraiser for the nonprofit “Facing History and Ourselves.” Facing History equips middle- and high-school teachers and administrators to embrace a thoughtful, rigorous approach to history to promote civic engagement, a sense of empowerment, and the investigative rigor to understand how injustice happens—so we don’t have to repeat past mistakes. Their training and curriculum resources encourage deep inquiry. They show students how to ask the tough questions. They foster in an entire school (not just a social studies classroom, which is super cool) an orientation toward challenging entrenched attitudes about race, bullying, homophobia, and other volatile topics. A young woman spoke at the fundraiser; she had studied with Facing History in high school and had just graduated from college. Her words were an inspiring lesson in honesty and bravery. She said her college “worked hard to get Latinx students there, but they didn’t make us feel welcome when we arrived.” She spoke of fighting to raise awareness of the issue, to help create safe spaces for Latinx students at her college, and of her vision to shape a career that combines her passion for reproductive rights with her concern for immigrant women.

History gives us many such role models of courage. Sandy and I recently went to a fundraiser for the nonprofit “Facing History and Ourselves.” Facing History equips middle- and high-school teachers and administrators to embrace a thoughtful, rigorous approach to history to promote civic engagement, a sense of empowerment, and the investigative rigor to understand how injustice happens—so we don’t have to repeat past mistakes. Their training and curriculum resources encourage deep inquiry. They show students how to ask the tough questions. They foster in an entire school (not just a social studies classroom, which is super cool) an orientation toward challenging entrenched attitudes about race, bullying, homophobia, and other volatile topics. A young woman spoke at the fundraiser; she had studied with Facing History in high school and had just graduated from college. Her words were an inspiring lesson in honesty and bravery. She said her college “worked hard to get Latinx students there, but they didn’t make us feel welcome when we arrived.” She spoke of fighting to raise awareness of the issue, to help create safe spaces for Latinx students at her college, and of her vision to shape a career that combines her passion for reproductive rights with her concern for immigrant women.

Light one candle for the strength that we need

To never become our own foe

And light one candle for those who are suffering

Pain we learned so long ago

The event concluded with a conversation between Jonathan Eig, whose recent biography of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. has met with critical acclaim, and Adam Green of the University of Chicago, whose scholarly work includes post-emancipation African-American history, cultural studies, and urban studies. The conversation was about Dr. King’s legacy for us in our time; it was fascinating, and I felt stretched in a wonderful way afterward. The conversation took a deep dive into, among other things, our tendency to put leaders on pedestals; the seminal influences on King’s life and thinking, including Coretta Scott King and Rosa Parks; and King’s own way of stretching himself to take on bigger and bigger problems, even when it was very difficult, and of continuing to find and engage with people whose views differed widely from his own, including Stokely Carmichael and the toughest Vice Lords gang leaders in Chicago.

Light one candle for the terrible sacrifice

Justice and freedom demand

Toward the end of the conversation, Adam Green reminded the audience about Howard Thurman’s 1948 book, “Jesus and the Disinherited,” one of my favorite books. A mentor to Dr. King, Howard Thurman was dean of the chapel at Boston University and one of the most influential theologians of the 20th century. In this book, Thurman speaks to the downtrodden of the time: Americans of African descent, against whom Jim Crow relentlessly hurled insult upon humiliation upon pain upon injustice. However, rather than encouraging African Americans to succumb to rage, violence, hate, or disconnection, Thurman exhorted just the opposite: moral courage, a conviction that their own basic goodness, in concert with others, could turn the tide, and a sense, using Christian language, of “committing myself to the redemption of everyone.”

Echoing Gandhi, who said, “Nonviolence requires more courage than violence,” Dr. King said, “We will meet suffering with soul force.” When we do not follow the crowd by succumbing to fear or fearmongering, we can look our situation squarely in the eye and begin to tell the truth of the situation. Following this example, we must insist on goodness and truth-telling from ourselves first, holding ourselves to a higher standard rooted in compassion, what Abraham Joshua Heschel calls “moral grandeur and spiritual audacity.” This, in turn, creates a virtuous cycle of people committed to making the entire situation work for all concerned. I especially like how Buddhist nun Pema Chödrön describes King’s mindset: “For me to be healed, everyone has to be healed.” If my life gets better, but you are left in the dust, does that really work in the long run?

Light one candle for all we believe in

That anger not tear us apart

And light one candle to find us together

With peace as the song in our hearts

A worldview where we all mattered… what would our planet look like if that’s what we all strove for? How would we have to enlarge our sense of who “we” are if we wanted that sort of society? Can we challenge ourselves, individually and collectively, to do that? I’d like to find out. I’m not sure we can survive as a species if we don’t.

What all these wise people are pointing to is not conventional thinking, and I don’t claim to be good at it. If it were easy to create a bigger box that could hold us all, what King called “a revolution of values,” we would have done it by now. But I want that world: an America, for example, where I don’t have to choose between health insurance and food or between living in my car and paying rent and where I don’t have to endure ridicule for wanting that. I want a world where my character and skills matter more than my skin color. I want a world where caring for my children or parents doesn’t mean I have to quit my job. I want to be able to love whom I choose, make choices about my own body, and live with dignity in a place that I can afford. And of course, I want a world where the gifts and experiences of older adults are celebrated. It may take us still more centuries to “light one candle to find us together with peace as the song in our hearts,” but it’s the right direction. Let’s go there.

Don’t let the light go out!

It’s lasted for so many years!

Don’t let the light go out!

Let it shine through our hope and our tears.

“Light One Candle,” written by Peter Yarrow. Lyrics ©Warner Chappell Music, Inc.

©Jonathan Miller

when we can’t remember the name of the movie we just saw. But when I started hyperventilating with disabling anxiety in airports and receiving bizarre Chinese packages I’d ordered from ads on Face Book, I called Northwestern Hospital to see a

when we can’t remember the name of the movie we just saw. But when I started hyperventilating with disabling anxiety in airports and receiving bizarre Chinese packages I’d ordered from ads on Face Book, I called Northwestern Hospital to see a

togethers are often hilarious games of 20 Questions where we all guess what someone is trying to remember.

togethers are often hilarious games of 20 Questions where we all guess what someone is trying to remember.