In the early 1970s the doomsday prophecies in Hal Lindsey’s The Late Great Planet Earth, stoked my Toms River, New Jersey, Christian fundamentalist cult. Little did I know that the prophesies of the cult religion of my youth would come true through a new religious movement, the National Apostolic Reformation (NAR). Fifty years later.

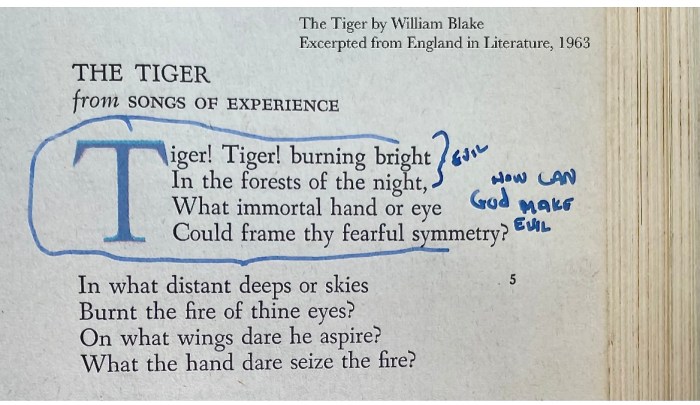

Based on his interpretations of the Book of Revelations, Hal Lindsey connected end-of-the-world Biblical prophecies to current events. In his view, Satan’s plans to form a one-world government and religion were triggered by the establishment of the state of Israel and the World Council of Churches—both in 1948.

Converts, like me, of the 1970s Jesus movement, still flash-backing to acid trips, saw signs of the end times around every corner. In our small church community, anti-globalism was our protest because Satan was using the banks to form a global economy. We boycotted the Bank of America. We refused to use credit cards. We wrote letters condemning the birth of the European Union. An increase in the divorce rate, recreational drugs, new technology, the gasoline shortage, religious ecumenism. All these signaled the diabolic end of the world, the coming of the Antichrist, or some kind of unearthly vision that terrified vulnerable young comfort-seekers.

I left the Christian cult after sobering up in Alcoholics Anonymous, divorcing an abusive husband, and moving 1,500 miles away from the scene.

Starting in the 1980’s, unbeknownst to me, Christian fundamentalism slowly morphed into the New Apostolic Reformation. The prime NAR chronicler, Matthew D. Taylor, describes the NAR’s leadership as a “spiritual oligarchy” of apostles and prophets. Apparently God has told NAR adherents that Donald Trump is their spiritual leader. You’ll have to figure that one out for yourself, but the results are obvious.

The NAR apostles and prophets tell Trump his job is to “advance God’s earthly kingdom so Christ can return.” Advancing the earthly kingdom is outlined in Project 2025. The elimination of abortion and women’s rights; same-sex marriage and gay rights; dismantling USAID as a stand against globalism—all the shockers in the first year of Trump 2.0 are advancing the earthly kingdom.

Venezuela is the biggest shocker so far, at least for me. Fifty years ago I learned that the Book of Revelations prophesied God would make the United States, Russia and China the world’s three spheres of influence. The United States would get the entire Western Hemisphere. Russia gets its region, and Europe. China gets all of Asia, India, Africa. This is the umbrella of national sovereignty, the opposite of international integration and the seeds of anti-globalization.

A radio broadcaster startled me on Saturday morning, January 3, with the news that the US invaded Venezuela. The long-forgotten voice of myself as a 25-year-old Jesus Freak bellowed, “Uh. Oh. Wake up. It’s happening.”

Donald Trump, in a 2017 speech to the Joint Congress, announced he was not the President of the world. Instead, he stated, he was the President of America. These words sent a signal to anti-globalists and end-times prophets around the world. It was a declaration that the US will once again dominate the Western Hemisphere. Vladimir Putin confidante Alexander Dugin, heard the call and issued a statement that traditionalism had won, globalism lost.

Anthropologists say pandemic uncertainty, virtual reality, environmental issues, old-age anxiety, border disputes, memory disorder, and gender trouble put society in a self-protective liminal state, a state betwixt and between. Perhaps these unsettling markers ushered in Donald Trump as the leader of the new world order. Now that we’ve fallen over the threshold, what do we do?

I don’t know.

But holy shit.

Wake up.

It’s happening.