One of the first gifts I received from my grandson, CJ, was his framed eighth grade self-portrait. He filled the center of a twelve by sixteen inch paper canvas with his life-size face, neck and shoulders, probably as instructed by his teacher. The background is a collage of his own black & white photos, trees and fences, angled every which way. The drawing portrays what he looked like at thirteen years old.

Except he painted himself cobalt blue.

This painting hangs from a hook on the wall-to-wall bookcase in my living room. CJ is fair-skinned with reddish-blonde hair. I’ve never asked him why he painted himself cobalt blue. As far as I know, he wasn’t imitating Picasso’s blue period. No one knew about the blue people of Kentucky until the 2019 publication “The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek.” After hearing so many ads for Blue Man Group on TV, CJ expressed interest in seeing them live on stage. But it was an interest, not an obsession.

![]()

Cobalt blue, used for centuries by the Chinese for their blue and white pottery, is the epitome of coolness; dark, deep, and mysterious. It’s the color of the evening sky in winter, clear twilight boosted by the unseen sun from below the horizon. CJ’s not the only creative to fancy cobalt. J. M. W. Turner, Renoir, Claude Monet, and van Gogh all favored its compatibility with other colors. Remember Maxfield Parrish’s famous Daybreak? He used cobalt blue mixtures for the skyscape.

Public opinion polls show blue as the favorite color of both men and women. And yet, a case of the blues refers to feelings of sadness. My parents used the term, the blues, to announce their alcoholic hangovers.

Thanks to old African American traditions, the blues generally signify sadness without despair. Pastor Otis Moss III of Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago preaches about a blue note faith, one that’s rooted in letting dark times exist side-by-side with hope. Moss teaches his congregation to let these dark moody blues move around them while they practice dancing in the dark. This practice keeps the blues from turning to hopelessness and death by despair.

For the past ten years CJ’s self-portrait has hung where I see it everyday. He’s melded into my unconscious seeing. He looks the same to me. But as I write this and inspect him further, I see the cobalt blue has faded to dark teal. Teal is a modern color, one not seen in art before the twentieth century. It has no meaning really, except a lot of European TV shows use teal interiors and costumes. It makes the actors look better.

In real life, CJ’s hair has turned brown, but I still think of him as reddish blonde, just as his self-portrait will always be cobalt blue. We don’t see each other often in these isolating covid days. He’s in those perilous twenties where the blues start taking root.

I hope he’s dancing in the dark.

When the devils throw blow-out parties, they wave around essential-fatty-acid credentials weaving stories that depict the decolorization of human goodness. They bob around spewing certainties on the demise of the Democratic Party and the catastrophe of melting polar ice caps. Then they buzz cut what’s left of our serenity pronouncing Trump will be the next president.

When the devils throw blow-out parties, they wave around essential-fatty-acid credentials weaving stories that depict the decolorization of human goodness. They bob around spewing certainties on the demise of the Democratic Party and the catastrophe of melting polar ice caps. Then they buzz cut what’s left of our serenity pronouncing Trump will be the next president.

Ageism and age discrimination are different. Age discrimination raises its ugly head in institutions, corporations and housing. Experts often refer to ageism as complex and subtle. It is subtle, but not that complex. When someone addresses us as “young lady”, the implication is that young is good, old is bad. If we act flattered, we’re perpetuating the stigma. The expression “senior moment” aims to joke about aging memory loss as if it is an embarrassment rather than a normal part of getting old. One of our neighbors is often called “young at heart”. She’s an eighty year old woke grandmother who likes Chance the Rapper and marches in anti-racism demonstrations. “Young at heart” diminishes the lifelong experiences that have brought her to her own reckonings. Yes, ageism is subtle, but really, it’s not so complicated.

Ageism and age discrimination are different. Age discrimination raises its ugly head in institutions, corporations and housing. Experts often refer to ageism as complex and subtle. It is subtle, but not that complex. When someone addresses us as “young lady”, the implication is that young is good, old is bad. If we act flattered, we’re perpetuating the stigma. The expression “senior moment” aims to joke about aging memory loss as if it is an embarrassment rather than a normal part of getting old. One of our neighbors is often called “young at heart”. She’s an eighty year old woke grandmother who likes Chance the Rapper and marches in anti-racism demonstrations. “Young at heart” diminishes the lifelong experiences that have brought her to her own reckonings. Yes, ageism is subtle, but really, it’s not so complicated.

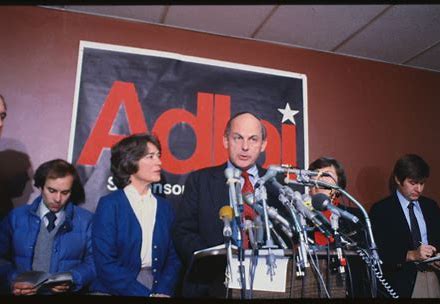

Adlai ordered another martini, a steak, baked potato and a salad. We ordered nothing. We had a lot of ground to cover, and food and drink would be in the way. When the second martini arrived, Adlai asked for beer with dinner.

Adlai ordered another martini, a steak, baked potato and a salad. We ordered nothing. We had a lot of ground to cover, and food and drink would be in the way. When the second martini arrived, Adlai asked for beer with dinner.