Facebook told me this the other day—that talking to my dog is a sign of intelligence. Whew. I’m glad of that. I talk not only to my dog but to all dogs. Out loud. In public. On the street. I’ve questioned whether their tethered humans might think I’m crazy but I can’t help it. It’s an irresistible impulse, a compulsion, this talking to dogs. And now I know it’s smart.

“Thank you for saying hello to me,” I say to the miniature poodle springing up and down in boyish spirals in the elevator.

“Mac, Mac, come see me,” I yell to Angie’s labradoodle on the sidewalk.

“Henry! Here comes that German Shepherd. Hang tight. Let ‘im sniff. Uh. oh. That scrappy Spitz. Just go ‘round him.”

The word for this is anthropomorphism. Facebook quoted behavioral scientist Nicholas Epley, a University of Chicago anthropomorphism expert. He says that I and others like me are actually showing signs of “intelligent social cognition” in talking to our pets. Because God made us social creatures, we talk to things we love, to be social, to have friends. For thousands of years dogs have adapted as companions to humans. They want to bond with us too, to be a part of the family, to please us. They even want to talk to us, which is why they bark. Dogs evolved from wolves. Wolves howl. They don’t bark.

Somewhere along the evolutionary highway, dogs learned to bark to communicate with their human packs.

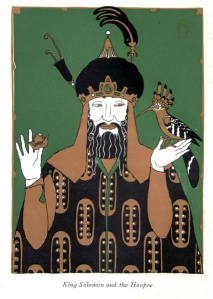

Literature old and new is full of talking animals. Some writings are called fables as in Aesop’s The Hare and The Tortoise, who challenge each other to a race. Some are fairy tales—the big bad wolf misleading a red-caped girl in the woods. Snakes and donkeys converse with humans in the Bible. The Koran says Solomon communicated with birds. How could all these stories be based on non-facts? Surely humans once chitchatted with both household pets and wild animals.

Henry retired at seven years old as a West Highland Terrier stud. His official registered name was Clipper. My friend, John, drove me to Indiana Amish country to fetch the castoff sire. I sat in the back seat with the dog on the way home so I could talk to him, bond. It was the month I first feared I was slipping into cognitive decline.

“He’s not responding to the name Clipper,” John said. “I’ll bet they never called him that. They just bred him. Why don’t you call him something like Henry?”

And so I did. All the way home to Chicago. The next morning I hollered, “Henry?” He ran from the next room and jumped in my lap. We’ve been conversing ever since.

I suspect the non-pet owners who find me talking to Henry when the elevator door opens haven’t heard of Dr. Epley’s research. To them, I’m just the batty old pensioner with the  fluffy white dog on the third floor.

fluffy white dog on the third floor.

But I know better.

I talk to animals.

Wonderful essay Regan. I talk to every dog I pass in the sidewalk or encounter in my building. Also cats. Fr. Felix S.J. and I have long conversations, but his mother is a Siamese and he inherited her loud vocal qualities as well as her “I am the Guardian” of this condo imperative.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Of course you talk to dogs. So do I. In face, I talk to dogs, and birds, and squirrels and rabbits (warning the latter two about Reilly’s likelihood of chasing them. Sometimes butterflies, bees and plants. Humans are the ones you have to decide whether to converse with. All the others are welcoming.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Special

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLike

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

No wonder you are so smart. That intelligence shows in this essay, so many clever turns of phrase: “tethered humans, “evolutionary highway.,” My absolute fave?:”University of Chicago anthropomorphism expert.” I’d say more here, but feeling a little slow-thinking and sluggish this Saturday morning. Need to have a talk with Whitney.

_____

LikeLiked by 1 person

Henry is lucky to have you….Dr. Dolittle. Great story!

LikeLiked by 1 person